Comments

When I was in fourth grade, if you finished your work early you got to go to the library. My favorite spot in the library was the mythology corner. There were three books in a series that retold the Greek, Roman, and Norse myths. And I read and re-read them. When my parents found out they asked me what I thought myths were, and I said I thought they were stories that people told each other to explain things that they didn’t understand.

Freshman year of college I planned to major in physics, but eventually I majored in the anthropology of storytelling. And among the books in our syllabus was Jung’s Memories, Dreams, and Reflections, which is a kind of a memoir written by him and his longtime personal secretary Aniela Jaffe. I was briefly introduced to Tarot during that time. At a social gathering a classmate produced a Tarot deck and prevailed upon each of us to exchange a single card. I was given the Page of Cups, who I came to refer to as a “student of sentiment.”

Fast forward about 30 years….

Around the year 2000 we were vacationing on St. Maarten in the Caribbean and stopped in a cluttered shop on Back Street in Phillipsburg I stumbled on a Marseille Tarot deck – the version of Tarot that the web application is based on. It was different from the deck my friend had in college – which I learned had been what’s now called the Rider-Waite-Smith deck. The Marseille deck seemed older, which it is, and stranger, which it also is. But that began or renewed my interest in Tarot. That was also around the time that I seriously thought about and investigated becoming a Jungian analyst. I had recently left a high pressure corporate job and was reassessing my life – what my wife calls a midlife crisis. I went so far as to get an application, but when I learned it was a seven year commitment I decided I’d continue to pursue my interest as an avocation.

The Tarot (or Tarrochi) deck originated for use in a card game similar to Bridge or Pinochle in which tricks are taken and a trump card must be played if the player can’t follow suit. The earliest recorded reference to the rules of the game is in a manuscript attributed to Martiano da Tortona, tutor to Filippo Maria Visconti, who became the Duke of Milan. Da Tortona died in 1425, so the document predates that.

The earliest playing cards were probably Chinese, originating after paper began being used to make items similar to dominoes or mahjong tiles that were previously made from ivory, stone, or wood. But the suits were organized differently and it seems that they could only have been remote ancestors of European playing cards. Overlapping the date of the first written reference to Tarrochi, large swaths of the Middle East were controlled by an ethnically diverse group of freed soldier-slaves known as the Mamluks. From 1250-1517 they controlled parts of Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, and reached as far as India.

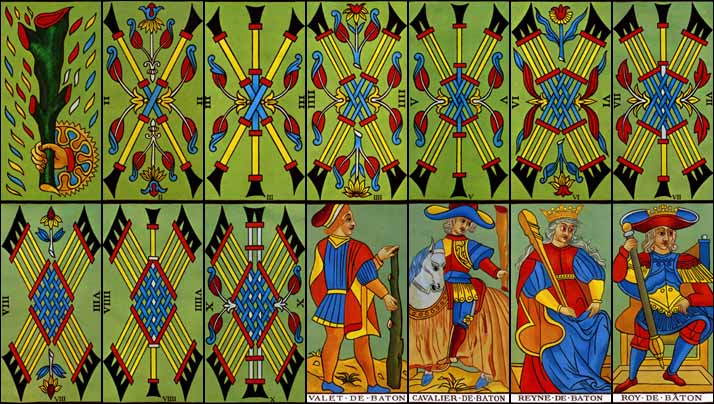

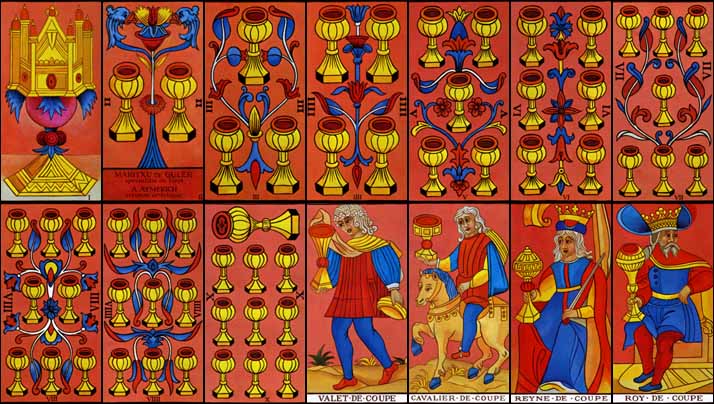

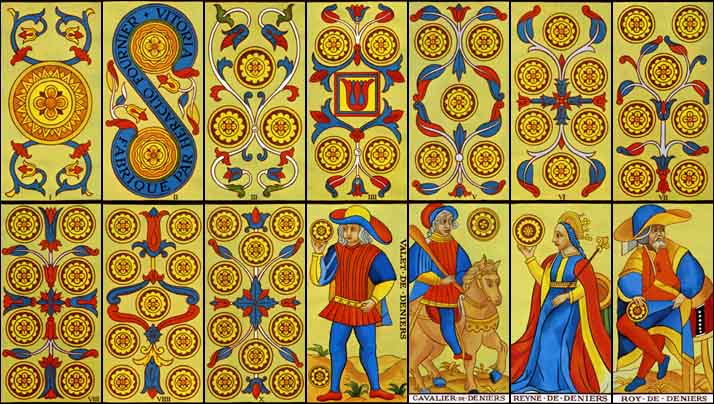

In 1939 a Mamluk card deck was discovered in the Topkapi Museum in Istanbul. The suits were: swords (which were curved), polo sticks, cups, and coins – clearly corresponding to the Tarocchi decks found in Italy in the 15th century. Polo sticks became “batons,” apparently because polo was not popular in Europe at the time the decks were introduced. Mamluks who served in the sultan’s household held a number of traditional positions -- among them were cup bearer, sword bearer, keeper of polo sticks -- but they could also become household treasurers, major-domos, keepers of the wardrobe, etc.

The Mamluks or people from areas controlled by them traded with Italy, and the assumption is that they brought Tarrochi cards to Milan. In 1499 the French invaded Milan, and Tarot was introduced into southern France some time after that. The oldest existing examples of what’s now called the Tarot de Marseille date from 1650 and are in the French National Library.

The oldest reference to using Tarot cards for “divination” dates from 1781. (Oxford defines divination as “seeking knowledge of the future or the unknown by supernatural means.”) That’s not necessarily what we’re doing, but historically, the oldest existing work on Tarot for divination is in a section of a massive work titled “The Primitive World” by an 18th century ex-Protestant minister and Freemason named Court de Gebelin. He made a bunch of stuff up that unfortunately still continues to influence people interested in Tarot, including that the images in the Tarot cards could be traced to ancient Egypt, and that the historical proliferation of Tarot was related to the Gypsies. Neither is true.

Four years after de Gebelin’s book, another Frenchman named Jean-Baptiste Alliette, who was a seed merchant and printer, published a book under the pseudonym Etteilla (Alliette backwards), titled “How to Entertain Yourself with the Deck of Cards Called Tarot.” His book included instructions for placing cards on the table (“spread”) and assigned meanings to the cards. He also promoted the association between Tarot and ancient Egypt, which as we’ve said is not true. But something about the images in the cards captured people’s imagination, and the tradition of using Tarot cards for so-called divination began.

You can see that in the Major Arcana there are many archetypal images that show up in western and other cultures, and this is one of the places where we connect with the work of Jung. From Jung’s archetypal events we see death, and possibly marriage; from archetypal motifs we see maybe apocalypse; from archetypal figures we see various possibilities for fathers, mothers, the trickster (magician), devil, wise old man/woman, various maidens. But Jung regarded the list of archetypes as essentially limitless, in part because they blend into each other, and in part because of the principle of enantiodromia. In general usage enantiodromia refers to a tendency of things to turn into their opposites, but Jung used it to refer to the emergence of the unconscious opposite over time.

Jung himself acknowledged the resonance of the Tarot with archetypes. In his essay “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious” he wrote “It also seems as if the set of pictures in the Tarot cards were distantly descended from the archetypes of transformation.”

The way I’m evolving of working with Tarot cards – because it’s ongoing, and I’m also not the only person who works this way – is related to what Jung referred to as “amplification.” He used the word amplification to refer to a method of dream interpretation that compared the images in a dream to images from myths and other sources. In this case the spread is like the dream, and we develop an interpretation by drawing parallels to images and patterns in myth, history, literature, culture, and so on.

The card images are from Lucian Wischik who scanned them, and notes that he believes them not to be copyrighted.